Digital ID Workshop Summary – Kenya May 2019

OVERVIEW

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) and the Kenya Red Cross Society (KRCS) hosted a Digital ID High-Level Design Workshop in Nairobi, Kenya from May 27th to 29th, 2019. The workshop was supported by the Dignified Identities for Cash Assistance ( DIGID ) project as part of a wider market dialogue to learn about the opportunities, risks, and solution strategies for digital ID in the humanitarian sector.

The workshop was conducted in two parts bringing together participants from the humanitarian, government, and technology sectors to discuss, analyze, and forecast the utility of digital ID for humanitarian cash assistance in the context of Kenya. The KRCS estimated at least one quarter of their caseload as lacking an official or recognized form of ID.

A combination of presentations, group discussions, and scenario analyses focused participants towards achieving the workshop objectives.

PART 1: CONSULTATION WITH GOVERNMENT & FINANCIAL SERVICE PROVIDERS (FSP)

Governments and financial service providers (FSP) are key stakeholders in cash transfer programming and essential in designing a digital ID ecosystem. Governments are trust anchors providing foundational and legal forms of ID. Government issued ID is widely recognized as the most authoritative form of identity. FSP’s regularly make use of different forms of ID to identify and authenticate recipients of funds. FSP’s are also subject to legal regulatory requirements, which includes but not limited to Know Your Customer (KYC), Anti-Money Laundering (AML), and Counter-Terrorism Financing (CTF), where in many cases a government issued ID is required.

The objectives of this consultation were to:

- Identify efforts of Kenya FSP’s and government stakeholders in exploring or using Digital ID’s (policies, regulation impact)

- Identify opportunities for KRCS to collaborate with FSP’s and government stakeholders in using Digital ID to deliver humanitarian cash assistance (trust, acceptability)

- Identify risks that need to be mitigated when dealing with Digital ID’s

Key Discussion Points:

CHALLENGES WITH LACK OF RECOGNIZED ID AND KEY DRIVERS FOR DIGITAL ID’S

There was general agreement with the participants that identities are important and the risks to people with no official ID. One commented that “people with no ID’s are invisible”, consistent with one of the findings from the World Disaster Report in 2018. The government of Kenya has made efforts to register persons in the country and started to rollout the Huduma Namba , a biometric-based registration system feeding into a central database meant to be the “single source of truth on a person’s identity”. Such an identity system was to be linked with various services including banking, education, and healthcare to improve efficiencies in the “utilization of public resources”.

The workshop was steered towards the use cases for humanitarian assistance particularly for cash where beneficiaries with no official ID’s are not able to receive cash through FSP’s because of KYC requirements. The potential of digital ID’s to address KYC requirements particularly for humanitarian context needed to be explored more.

Another driver for digital ID’s is the need for empowering and enabling beneficiaries to manage and control their own data. With central repositories of data, the risk of data breaches is already high, but more importantly, once data is collected and stored there is no sense of ownership from the individuals on how their data is used, shared, or managed. Where an individual is not able to have full autonomy on their data, then the responsibility of institutions (government, NGO’s, FSP’s) to be custodians over their data will need to be strengthened and trust established.

It was expressed that the ultimate success of any digital ID initiative will depend on the end-users (affected individuals) themselves. They need to understand the value of their personal data and how they would benefit from a digital ID solution. One participant stated, “if [beneficiaries] realize the value, they will demand [the solution] from you.” Another participant commented, “data is power”.

OVERVIEW OF DIGITAL ID CONCEPTS

One participant asked whether we might be duplicating the efforts of the government to give digital ID’s to all citizens. We clarified that this was not the case. We differentiated the need for foundational & legal identities which the government is responsible for, and the functional identities that allow individuals to be identified and authenticated for very specific services such as cash assistance.

It was clear that to have an effective conversation about digital ID’s, certain concepts needed to be defined. Digital ID as a terminology itself was quite broad and participants had varying understanding on what it is. One of the participants, a representative from Gravity Earth , a technology provider implementing digital ID solutions in Kenya, helped introduce the concepts of digital ID such as credential, verification, guardianship, and self-sovereign identities. Self-sovereign ID (SSI) was particularly important as it promises to enable end users to have ownership and control of their personal data.

To address the challenge of lack of identity for humanitarian response, one option was to develop a mechanism to collect digital credentials such as a digital wallet that could be owned and managed by the individuals. Credentials are attributes about the individual (e.g. person’s name, or that the person is over 18 years old, or that the person belongs to a particular community) where credentials provided by institutions (e.g. Kenya Red Cross through their community verification) could be kept and presented when there is a need for verification to access a service or assistance. Presenting credentials does not mean divulging all the information you keep in your wallet, but rather presenting only the ones specifically asked for. E.g. an agency may simply need to know if a person is over 18 years old and does not necessarily need the exact birth date. A beneficiary can then show these credentials to other organizations or institutions to check if they are eligible for other services or assistance.

Data protection and Data responsibility

In discussing the Huduma Namba implementation, workshop participants indicated concerns from certain groups on the amount of information being collected during the Huduma registration process, and the potential risks related to how their data may be used and who will use them. This highlighted that data protection and privacy considerations are critical in designing digital ID solutions particularly for the humanitarian sector where potentially sensitive data of the most vulnerable are at stake.

One participant from the Netherland Red Cross’ 510 initiative shared their guidelines for data responsibility. It covered principles of “do no harm”, separation of personal and non-personal information, and applicable laws/regulations (e.g. GDPR). As recommended, efforts on digital ID’s should look at data protection both from the legal framework (laws) and that of the organization’s own internal policies. In Kenya, the Data Protection and Privacy policy was relatively new and the pace of technology may be outrunning regulation. For Kenya Red Cross, an internal policy was also in the process of being developed.

ACCEPTABILITY OF DIGITAL ID’S

When the participants were asked if there is a potential for the acceptance of digital ID’s or credentials issued by humanitarian organizations especially in fulfilling KYC requirements, the FSP representatives deferred to the government. The rationale was that if the government will allow the use of humanitarian digital ID’s, then there will be motivation to invest in systems and procedures to allow these digital ID’s in cash distributions via FSP’s. The financial services sector in Kenya is thriving and already quite advanced, but the challenge seemed to be that the laws need to keep up with the technology.

Government laws and intergovernmental laws would need to recognize the validity of different forms of digital ID’s in order for them to be leveraged to meet KYC, AML, and CTF rules, enabling access to financial services. One participant from a government organization noted that fundamental to achieving the benefits of digital ID is either adapting technology to existing law or reforming these laws in order to ensure that ID is actually functional.

We have seen instances in other contexts where humanitarian ID’s were accepted by the government and allowed them for certain services. For example in Uganda, refugees were allowed to use ID’s issued by UNHCR to access SIM cards. In 2015, WFP partnered with Safaricom and the Kenyan government to allow SIM cards to be distributed to refugees in the Kakuma camps to receive cash for food in local markets.

So what can be done to facilitate/accelerate the use of digital ID’s in humanitarian contexts?

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF), an intergovernmental task force created in 1989 by the G7 in order to develop policies to combat money laundering, released a report in November 2019, analyzing the potential for digital ID to fulfill each of these criteria, indicating a multi-sectoral movement towards providing financial services for the world’s population.

In another conversation with a government representative about the new Data Protection policy in Kenya, it was indicated that humanitarian organizations were not widely represented in the review process. It was added that the context for humanitarian purposes was important particularly in disaster emergencies, because of the lifesaving nature as well as a sense of temporary, time-bound activities. By working on advocacy with the government, there is a good chance for the acceptance of digital ID’s issued by humanitarian organizations.

It was recommended that the Kenya Red Cross, as an auxiliary to the government and already having strong partnerships with different ministries, regulators and even FSP’s such as Safaricom MPESA, conduct such advocacy discussions with the government and suggest piloting opportunities or partnerships on such efforts. Having a wider community of humanitarian actors will also strengthen the case for digital ID’s in the wider sector. Advocating for the most vulnerable which could lead not just to receive emergency assistance, but potentially better financial inclusion and a path towards legal identities.

Not only are laws important to change rules governing financial transactions, but also registration for critical enabling technologies like SIM registration. Change to legal and regulatory frameworks is slow, and participants cautioned against overly optimistic predictions about the near term benefits of digital ID’s.

RISKS WITH DIGITAL ID’S

Participants also noted that digital ID poses risks as they relate to data security, data protection, the management of personal data, and the loss of identity. Though each risk can be somewhat mitigated by technology, participants noted that many of these risks are, at bottom, a question of beneficiary digital literacy and can only really be mitigated by a holistic education campaign that seeks to build local awareness of the potential opportunities, and inherent risks, of digital IDs. One participant in particular noted that governments (not just humanitarian organizations) need to be involved in this process of beneficiary education in order to ensure that they reach critical mass.

Conclusion

Involving government and FSP representatives in the discussion around digital ID’s for humanitarian cash assistance is critical for any solution to be effective and scalable. We received insights on potential blockers and perceived risks, but also had a very productive discussion on possible way forward through advocacy, highlighting the humanitarian imperative, and partnerships. Most important perhaps was the comment around the value of personal data and education of end-users on the value of such a digital ID solution for them.

PART 2: WORKSHOP WITH HUMANITARIAN ORGANIZATIONS

Following the consultation with government and FSP representatives, a two-day workshop with NGO’s based in Kenya was conducted. The objectives of the workshop were to:

- Validate the pain points related to digital ID’s in cash context from beneficiaries and field perspective

- Gain familiarity with the concepts related to digital ID’s and emerging technologies

- Understand the different solution strategies and considerations that could address the pain points related to digital ID’s

The workshop had representatives from Kenya Red Cross, Save the Children, Norwegian Refugee Council, and Norwegian Church Aid. Guests from GSMA and private sector also attended. Like governments, NGO’s can act as trust anchors (verifiers and authenticators of identity). In certain contexts, for instance, UNHCR identity credentials have been leveraged to enable access to services previously only accessible via legal ID. These cases, though unique, illustrate the possibility that NGO’s could increasingly become trust anchors.

The workshop looked at the different types of data that humanitarian organizations are collecting and attempted to categorize the identity and programmatic data elements. The workshop also looked at the motivation of beneficiaries to manage their own data and requirements for achieving it, given that many of the affected communities reside in low-connectivity areas. On the NGO side, the motivation to share data and have interoperable systems was explored.

The outcomes of the workshop were used to develop the functional and non-functional requirements for the DIGID project.

Key Discussion Points:

CHALLENGES WITH IDENTITY IN CASH ASSISTANCE

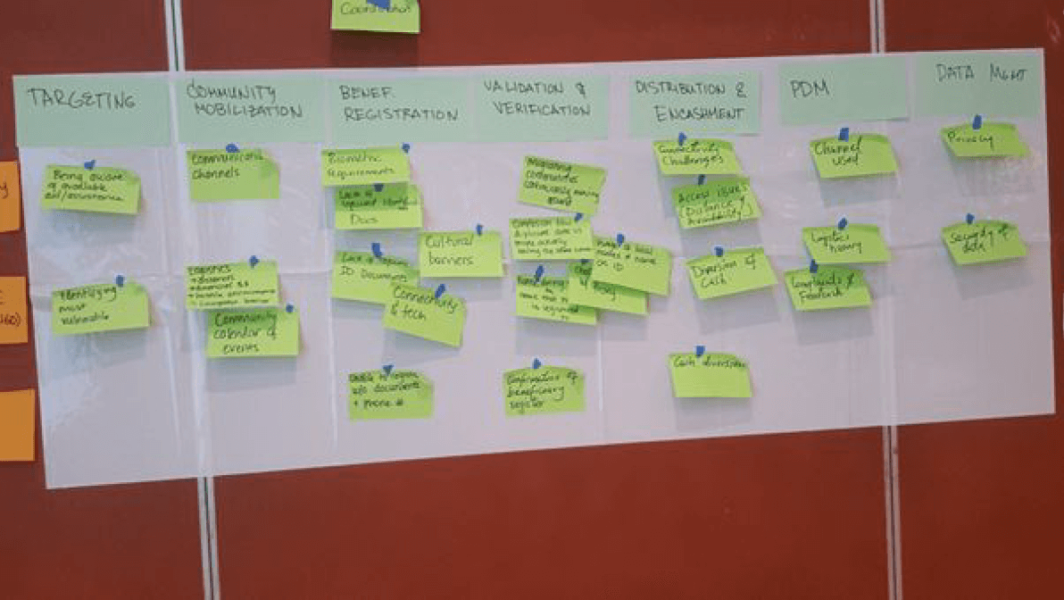

The workshop participants were put into groups and given a general, simplified version of a cash assistance process focusing on: targeting, beneficiary registration, validation/verification of registered beneficiaries, distribution & encashment, and post distribution monitoring. The groups were then asked to identify the pain points related to identities experienced by different stakeholders in the process, namely: the NGO field officer, the beneficiary, and the FSP representative. The figure below was from one of the groups.

Given that the participants were from different organizations, the process steps had to be clarified so everyone had the same baseline to work from. The exercise also highlighted not just identity related issues, but general issues in their corresponding internal processes. Some of the key issues related to identity highlighted were:

- Lack of informed consent from beneficiaries

- Insufficient data security

- Diversion of cash due to fraud or inability to verify identities

- Problems with having alternative recipients or proxies that receive cash on someone else’s behalf because of lack of official ID

- Beneficiaries excluded due to absence of legal identification

- Migration and refugee context becomes more complex without proper identification

- Some people are known by different names than their official name

- Duplication of data and difficulty in verifying which one is actually true

The exercise helped validate the user personas and user journey developed by the DIGID project highlighting the different challenges faced by the different stakeholders in the cash assistance process. The DIGID user personas and user journey were shared as part of the debriefing session after this exercise.

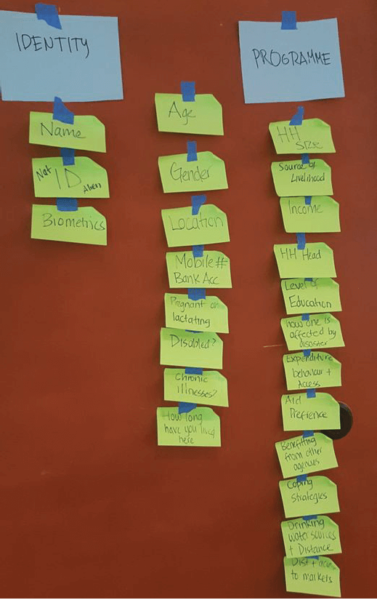

IDENTITY VS. PROGRAMME DATA

After validating what the issues were related to identities in a cash program, the participants were again asked to work in groups to identify what constitutes identity data and programme data. The exercise was meant to reflect on the types of data that humanitarian organizations typically collect and what we may define as identity-related data. An example from one of the groups is shown in the figure below. The sticky notes in the middle meant to indicate that they could either be both identity and programme data.

Out of the four groups, three of them indicated common elements under the “Identity” category: Name, National ID number, and biometrics data. Many elements were put in the middle category because they were likely to be both identity and programme data, as they could be used for programme decisions (e.g. targeting, eligibility, conditionality). One group categorized age, gender, and place of residence under “Programme” data, which sparked the discussion as what constitutes purely identity vs. programmatic data.

The discussion following the group work highlighted that humanitarian organizations are collecting many data points of which are personally identifiable. We do not normally just collect disjointed data for programme purposes e.g. source of income, expenditure behaviour. There is typically a linkage to personal data. It was also important to note that even without direct personal information as name or address, several data points could be combined together to potentially identify a person or household, making it more important to be conscious of how humanitarian organizations store and manage data whether we think they are only programmatic ones.

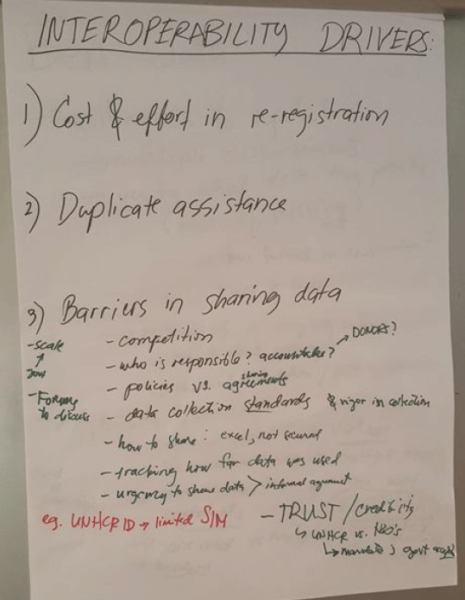

INTEROPERABILITY

Humanitarian organizations tend to solve the problem related to identities in silos, for the purposes of their own organization. We see agencies using different and separate data management systems addressing their own needs to identify, register, and authenticate individuals, with little to no sharing of data with other organizations. The DIGID consortium members for instance have different systems they are using, and in some of their delegations pen and paper or basic Excel spreadsheets are still used. Donors are asking for more transparency and efficiency and urge humanitarian actors to work closer together.

The impact to beneficiaries with the siloed approach is that multiple organizations conduct registration on the same communities, creating survey fatigue and possibly creating expectations of receiving aid. Additionally, beneficiaries have no direct access to data collected about them, and many are unsure on how their data is used and who they are shared with, making it difficult to assert their rights as data subjects. For digital ID’s to be effective and scalable, organizations will need to work collaboratively to solve the problem together and keep the beneficiaries at the center of the solution.

Interoperability for this workshop was explored through the following questions:

- Is there willingness for NGO’s to share data?

- Do NGO’s trust data from other NGO’s? Do they trust the verification process?

- Have NGO’s accepted identity related data from other NGO’s before? In what conditions?

- Are there cost savings in minimizing the registration process?

In general, there was agreement that sharing data between organizations is good in the spirit of coordination, reducing duplication and overlaps. There was agreement that costs in general would be lower if re-registration is avoided and there would be general efficiencies gained. But participants mentioned that there are barriers to such sharing of data including: competition, donor requirements, strict organizational policies, lengthy negotiations of data sharing agreements, lack of rigor in data collection (bad data quality), lack of standards in data collection, and inability to track how data will be used by third parties.

The discussion with the participants then focused on three areas to try to address the barriers mentioned: trust, standards, and data protection.

On trust, the participants were asked to reflect on examples when they have actively shared data with other organizations. The examples showcased formal and informal ways of sharing data and depended also on the type of data shared. For formal sharing, an agreement was typically signed. For informal sharing, basic beneficiary lists were shared to ensure timely, lifesaving response. The verification process of data collected by NGO’s could differ and may be subject to donor requirements. In certain scenarios where a National ID is not available, NGO’s rely on social verification, where certain authority figures are asked to vouch for individuals within a community. Trusting that one NGO has conducted thorough due diligence and verification methods would help speed up the process in assistance provision.

Another factor on trust mentioned was the mandate or role of an organization. For instance, UHNCR with mandate on refugees is seen as a trusted agency and therefore the refugee ID’s they issue are well recognized.

Standards was another important enabler for interoperability. It was mentioned that having standardized data collection models would help data sharing. But also standards in terms of the technology to allow for digital ID’s or digital credentials to be issued by one institution and be readable or recognized by another. Having strong mechanisms that would ensure that the credentials were not falsified and that the verifiers are known entities, help generate trust in the system where there could be numerous credentials being exchanged and processed.

Protection of personal data and privacy was also seen as enabler for effective interoperability in addition to strong data security. As humanitarian organizations, we operate on “do no harm” principle and thus have the duty to take care of the data of the most vulnerable as we become de facto guardians of their data. Having clear policies and understanding on how data will be shared securely and how they will be utilized by the agencies where privacy and data subject rights are preserved become important factors to trust whether or not to share data.

In this session, the key message was that a combination of technology and governance frameworks would be necessary to ensure trust and therefore effective interoperability between the actors issuing and using digital ID’s.

Furthermore, interoperability could be achieved by enabling individuals to hold and manage their data. If the individual sits at the center of all the NGO’s they interact with, and all NGO’s can access de-identified information on that individual, then NGO’s could cohere their programming around shared objectives and common goals. In order to do so, however, participants noted that humanitarian organizations will need to build trust in themselves as data processors, and in individuals, themselves, as end-line managers of data. One participant in particular noted that, by placing data in the hands of the beneficiary, it would be possible to create a common reference point for several NGO’s, making it possible to organize programming and optimize for efficiency.

WILLINGNESS OF BENEFICIARIES TO MANAGE THEIR OWN DATA

Empowering end-users (affected individuals) to own and manage their own data is a strong value proposition for the use of digital ID’s particularly self-sovereign identities. But what is the motivation of affected individuals to keep and manage their own data?

During the discussions, we heard of examples of beneficiaries holding on to the temporary beneficiary cards provided for distribution purposes by NGO’s. And in some cases, beneficiaries have used those cards as proof of identity to other NGO’s, even though they were not meant as an identity document but rather a token for distribution. This illustrates the value of having an artifact that could act as an identifier. It’s also important to highlight the trust they have to the organization that issued such an artifact. This demonstrated the value of ownership of their information.

In terms of managing their own data, the participants did not have concrete examples to show the willingness of beneficiaries to manage their own data. A question was posed, “could there be motivation to be registered multiple times if that means higher probability to receive multiple benefits from different actors?” Some participants reiterated the importance of literacy and education and the fact that traditionally, agencies would just come to collect their data. Going back to the previous example of a beneficiary going to other NGO’s to show that they have received assistance and been identified by a trusted institution, linking this opportunity to receive further assistance or services by just showing credentials, could lead to more willingness and active attempts for beneficiaries to manage their own data. This also points to the dignity we offer to provide quality service to the most vulnerable by showing them that there are better and faster ways to access services than constantly going through multiple registrations.

DIGITAL ID’S IN LOW-CONNECTIVITY SCENARIO

An important question to help determine the scalability and usefulness of digital ID’s for humanitarian context is, “how will the technology work in difficult environments (low connectivity settings) where the most vulnerable typically reside, and who may not have access to the latest technology such as a smartphone or even a feature phone?” The concept of a pure self-sovereign identity (SSI) seems to require good access to established infrastructure and smartphones to manage digital credentials (or at least the current technology available for this). Also, from an NGO perspective we need to be conscious of the funding and resource constraints to invest in new technologies and allow for adoption by the organization.

One key consideration discussed in the workshop is the importance of having a modular approach and trying to see how to introduce a digital ID solution in an existing ecosystem rather than replace or change a lot of things including processes for the sake of the solution. For instance, many organizations might be using their own databases or beneficiary data management systems and applications that work offline. One step would be to analyze how the data collection of personal information may change and where that data should reside in the future, then figure out the integration of the digital ID system with the existing databases (if they are still needed).

In the case of Kenya Red Cross using KOBO for data collection in low connectivity areas, could they continue using that method and have a way to generate the digital ID’s later when there’s better connectivity? Would KRCS have to start storing only the references to the digital ID’s of beneficiaries in their data management systems to minimize the actual personal data stored in centralized databases? Will KRCS need devices that could work offline when reading digital ID credentials to verify beneficiaries or during distribution? Can KRCS integrate their existing biometrics systems with the digital ID platform?

A detailed analysis and possibly more research on the feasibility of SSI in low connectivity settings are needed. But the acceptability of such a digital ID solution will depend on how easy it would be to integrate with the existing technology architecture and with current processes of the organization–bridging a path from guardianship model to a self-sovereign model when the appropriate infrastructure and literacy levels are established.

CONCLUSION

The workshop allowed different stakeholders (humanitarian, private sector, government) to discuss current challenges related to identities and innovative ways, opportunities, and risks with digital ID in a specific humanitarian use case: to deliver cash assistance in Kenya. Participants gained an understanding of the basic concepts related to digital ID and the technologies (emerging and established) underpinning their implementation. Participants also discussed the major barriers to implementing these systems from both a beneficiary and a field implementation perspective, and the considerations for different solution strategies that could mitigate such challenges related to digital IDs.

An important outcome of the workshop was the documentation of key considerations for developing a digital ID solution for cash assistance, which was then translated to requirements used in the tendering process for the Dignified Identities for Cash Assistance ( DIGID ) project. For the list of requirements, please see the Request for Proposal published by the DIGID project.

Contact:

Joseph Oliveros | Cash Transfer Programming Innovations

International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC)

Chemin des Crêts, 17 | 1209 Petit Saconnex | Geneva | Switzerland

www.ifrc.org – joseph.oliveros (ifrc.org)

Safia Verjee | Innovations Manager

Kenya Red Cross Society

verjee.safia (redcross.or.ke)

www.redcross.or.ke | www.icha.net